Emily Costello, The Conversation and Thalia Plata, The Conversation

In some religions, women are barred from serving as clergy or excluded from top leadership roles. Nonetheless, women have broken into influential roles in these male-led faiths. How are these women forging new pathways in these traditionally patriarchal religions?

The Associated Press, Religion News Service and The Conversation held a webinar with academics, journalists and religious leaders to discuss the future of women in faith leadership on Dec. 9, 2021.

The panel featured Ingrid Mattson, chair of Islamic Studies at Huron University College at Western University; Emilie M. Townes, dean and distinguished professor of Womanist Ethics and Society at Vanderbilt Divinity School; Carolyn Woo, distinguished president’s fellow for global development at Purdue University; and Jue Liang, visiting assistant professor of religion at Denison University. Roxanne Stone, managing editor of Religion News Service, acted as moderator.

Below are some highlights from the discussion. Please note that answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Some of the women [faith leaders I’ve spoken] with [talk] about how leadership isn’t just in titled positions, but in influence. What is your definition of leadership? In the male-led faiths that you’re paying attention to, are you seeing any examples of women taking on nontraditional, unofficial leadership roles?

Carolyn Woo: I think leadership is the ability to have a vision that really advances that particular organization and serves that organization, and the capacity to translate that vision into action. I think influence is very important. I think informal influence for women comes from the fact that perhaps [they] are very invested with [their] work and have expertise and have good relationships with people and credibility. Those are informal sources of influence, but it is not fair. Women shouldn’t only operate with informal power – not because it is not useful, but because they also deserve formal recognition of their position. Formal positions allow you to have a vote. You don’t have to whisper it to somebody else.

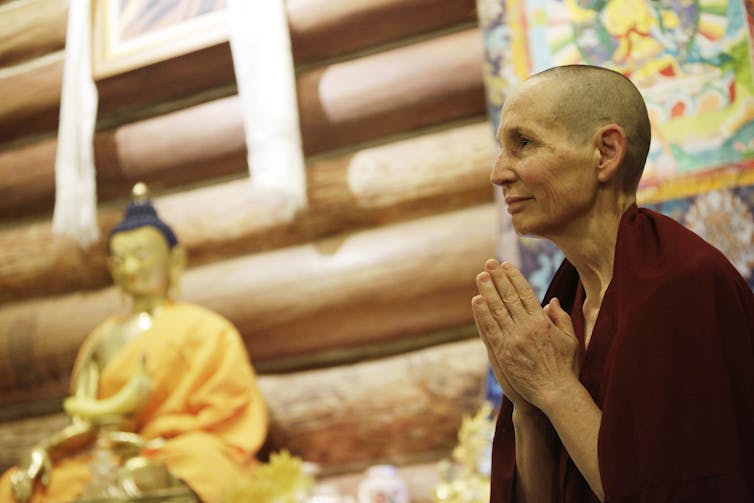

Jue Liang: The Buddhist way of thinking about leadership is more in the identity or the role of a teacher or a role model. Everyone has the potential to become enlightened, just like the Buddha. [In Buddhism] leadership is considered, at least in theory, open to all. [Historically, it has not been] the case. But through education and ordination, we’re [seeing] more [role] models that are inhabiting the body of women. [Leading] more women to think, “Maybe I can do that too.”

Are women who have informal or non-clergy roles of influence – say in publishing, social media or academia – able to maintain that informal influence long term?

Emilie M. Townes: I think our ability to lead and influence is going to be tenuous [in any circumstances]. Influence is always going to be dependent on whether or not people are listening. I think it becomes even more tenuous if you are in a more conservative setting that has a hierarchy of roles where the thought of challenging is just not a part of everyday life.

Ingrid Mattson: I see a lot of self-censorship. When I speak to women religious leaders about issues that impact women, there’s a lot of caution that the majority exercise. They feel like their authority is very tentative and that all it takes is a few guys calling them a radical feminist [to lose their influence]. The women who are ready to step out have other sources of support. They are at universities or women’s organizations, so that even if they are dismissed in this way, they still have a basis for support.

When we talk about these issues [that women in male-led major religions face], there is almost an assumption that change is inevitable, that younger generations are just not going to stand for this. And that if women do not start to have more top leadership posts in some of these traditions, that they’re not going to survive. What are your thoughts on that, and where do you think we’re headed?

Carolyn Woo: Changes are inevitable, but the direction and the sources of those changes are not homogeneous. You have young people who walk away from the church and become disaffiliated. On the other hand, I also see women who have started ministries for women athletes. Within the Catholic Church, [women have started ministries] to try to understand our own menstrual cycles so that they could appreciate the female body.

Emilie M. Townes: Change is happening, but I always look at the structures of the change happening. [We may have more women seminary students than men], but if the basic structure of the church remains the same, the roles perpetuate the structure. I like to think more in terms of transformation. I think it pushes us further along.

Watch the full webinar to hear more detailed answers to these questions and to hear the panelists discuss stereotypes women leaders face, the future of women’s leadership in the Catholic Church, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Muslim women leaders and more.

[The most interesting religion stories from three major news organizations. Get This Week in Religion.]![]()

Emily Costello, Managing Editor, The Conversation and Thalia Plata, Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of AmericanScience.org.