Chris Curran, Northern Kentucky University

Scientists have often invited the public to see what they see, using everything from engraved woodblocks to electron microscopes to explore the complexity of the scientific enterprise and the beauty of life. Sharing these visions through illustrations, photography and videos has allowed laypeople to explore a range of discoveries, from new bird species to the inner workings of the human cell.

As a neuroscience and bioscience researcher, I know that scientists are sometimes pigeonholed as white lab coats obsessed with charts and graphs. What that stereotype misses is their passion for science as a mode of discovery. That’s why scientists frequently turn to awe-inducing visualizations as a way to explain the unexplainable.

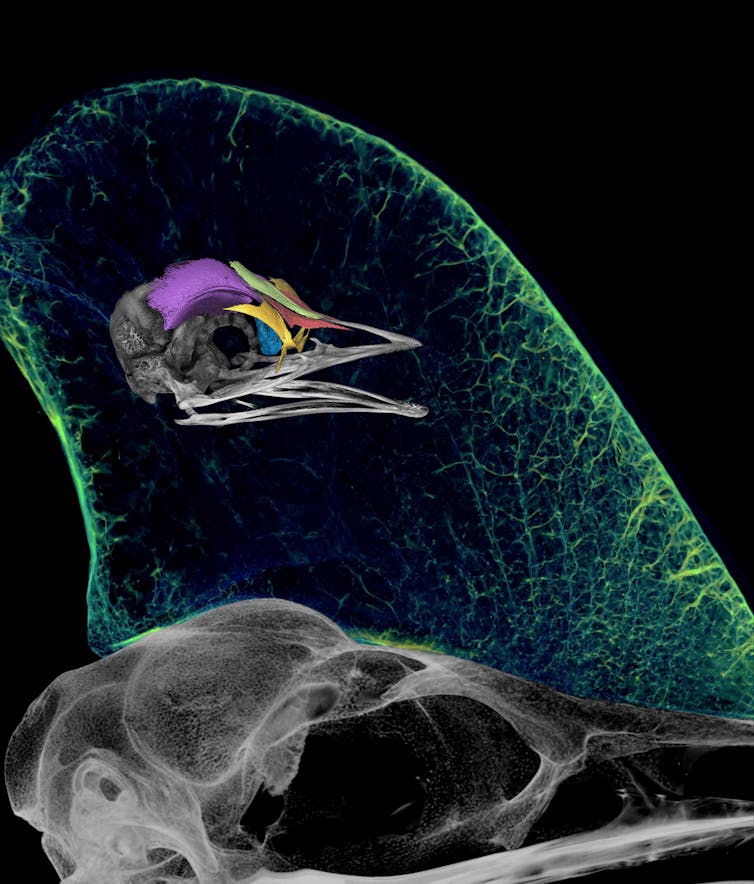

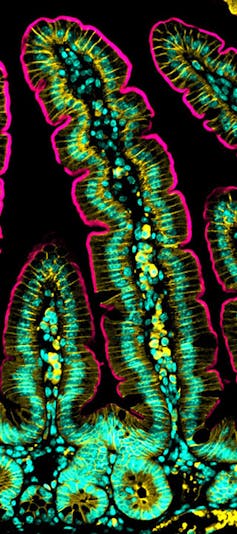

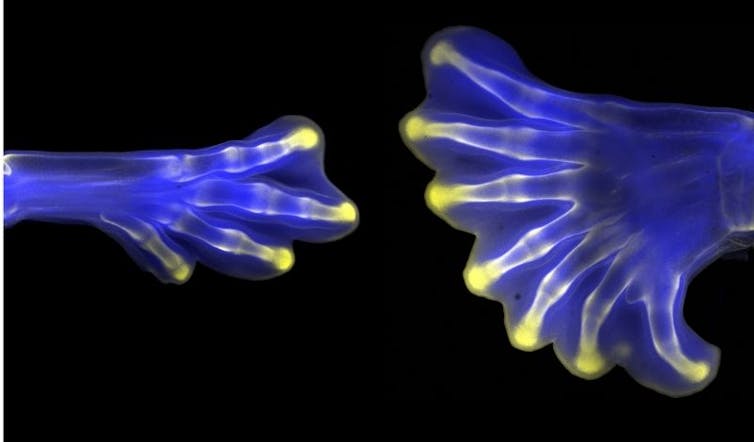

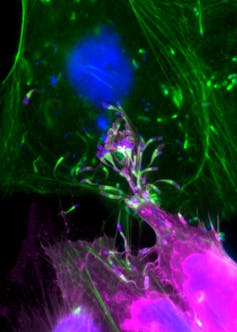

The BioArt Scientific Image and Video Competition, administered by the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, shares images rarely seen outside the laboratory with the public in order to introduce and educate laypeople about the wonder often associated with biological research. BioArt and similar contests reflect the lengthy history of using imagery to elucidate science.

A historical and intellectual moment

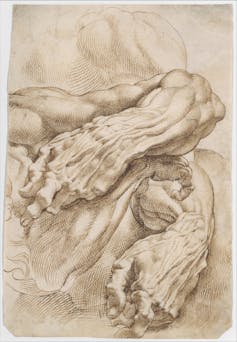

The Renaissance, a period in European history between the 14th and 17th centuries, breathed new life into both science and art. It brought together the fledgling discipline of natural history – a field of inquiry observing animals, plants and fungi in their ordinary environments – with artistic illustration. This allowed for wider study and classification of the natural world.

Artists and artistic naturalists were also able to advance approaches to the study of nature by illustrating discoveries of early botanists and anatomists. Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, for example, offered remarkable insight into human anatomy in his famous anatomical drawings.

This art-science formula was further democratized in the 17th and 18th centuries as the printing process became more sophisticated and allowed early ornithologists and anatomists to publish and disseminate their elegant drawings. Initial popular entries included John James Audubon’s “Birds of America” and Charles Darwin’s “The Origin of the Species” – groundbreaking at the time for the clarity of their illustrations.

Publishers soon followed with well-received field guides and encyclopedias detailing observations of what were seen through early microscopes. For example, a Scottish encyclopedia published in 1859, “Chambers’s Encyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People,” sought to broadly explain the natural world through woodblock illustrations of mammals, microorganisms, birds and reptiles.

These publications responded to the public’s demand for more news and views of the natural world. People formed amateur naturalist societies, hunted for fossils, and enjoyed trips to local zoos or menageries. By the 19th century, natural history museums were being constructed around the world to share scientific knowledge through illustrations, models and real-life examples. Exhibits ranged from taxidermied animals to human organs preserved in liquid.

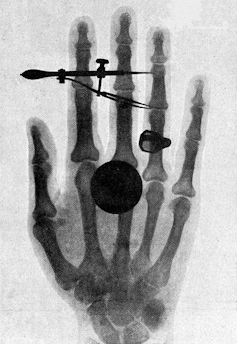

What began as hand drawings has morphed over the past 150 years with the help of new technologies. The advent of sophisticated imaging techniques such as X-rays in 1895, electron microscopes in 1931, 3D modeling in the 1960s and magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI in 1973 made it easier for scientists to share what they were seeing in the lab. In fact, Wilhelm Roentgen, a physics professor who first discovered the X-ray, made the first human X-ray image with his wife’s hand.

Today, scientific publications including Nature and The Scientist have taken to sharing their favorites with readers. Visualizations, whether through photography or video, are one more method for scientists to document, test and affirm their research.

Science, art and K-12 education

These science visualizations have found their way into classrooms, as K-12 schools add scientific photographs and videos to lesson plans.

Art museums, for example, have developed science curricula based on art to give students a glimpse of what science looks like. This can help promote scientific literacy, increasing both their understanding of basic scientific principles and their critical thinking skills.

Scientific literacy is especially important now. During a pandemic in which misinformation about COVID-19 and vaccines has been rampant, a better understanding of natural phenomena could help students learn how to make informed decisions about disease risk and transmission. Teaching scientific literacy gives students the skills to evaluate the claims of both scientists and public figures, whether they’re about COVID-19, the common cold or climate change.

However, science knowledge appears to be stagnating. The 2019 National Assessment of Education Progress measures the science knowledge and scientific inquiry capabilities of U.S. public school students in grades 4, 8 and 12 from a scale of zero to 300. Scores stagnated for all grades from 2009 to 2019, hovering between 150 to 154.

[Too busy to read another daily email? Get one of The Conversation’s curated weekly newsletters.]

A survey of K-12 teachers shows that 77% of elementary teachers spend under four hours a week on science. And the 2018 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education found that K-3 students receive an average of only 18 minutes of science instruction per day, compared to 57 minutes in math.

Making science more visual may make learning science at an early age easier. It could also help students both understand scientific models and develop skills like teamwork and how to communicate complex concepts.

Deepening scientific knowledge

The BioArt Scientific Image and Video Competition was established 10 years ago to both give scientists an outlet to share their latest research and allow a wider audience to view bioscience from the researcher’s point of view.

What’s unique about the BioArt competition is the diversity of submissions over the past decade. After all, bioscience encompasses the wide range of disciplines within the life sciences. The 2021 BioArt contest winners range from a zebra fish embryo’s developing eye to the shell of a species of 96 million-year-old helochelydrid fossil turtle.

I have served as a judge for the BioArt competition over the past five years. My appreciation for the science behind the images is often exceeded by my enjoyment of their beauty and technical skill. For instance, photography using polarized light, which filters light waves so they oscillate in one direction instead of many directions, allows scientists to reveal what the otherwise hidden insides of samples look like.

Whether today or in the past, science elucidates the foundation of our world, both in miniature and at scale. It’s my hope that visually illuminating scientific processes and concepts can advance scientific literacy and give both students and the general public access to a deeper understanding of the natural world that they need to be informed citizens. That those images and videos are often beautiful is an added benefit.![]()

Chris Curran, Professor and Director Neuroscience Program, Northern Kentucky University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of AmericanScience.org.