Sylvia G. Dee, Rice University

Long before the current political divide over climate change, and even before the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865), an American scientist named Eunice Foote documented the underlying cause of today’s climate change crisis.

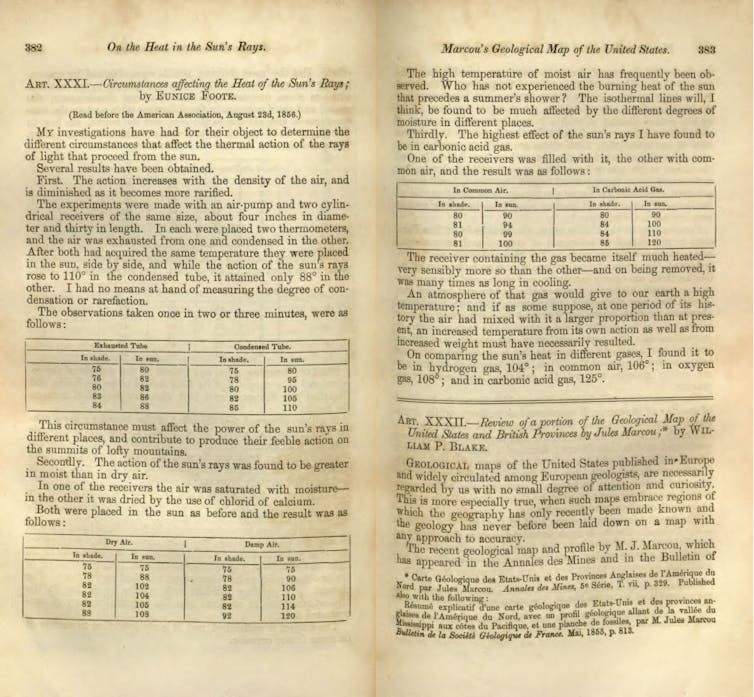

The year was 1856. Foote’s brief scientific paper was the first to describe the extraordinary power of carbon dioxide gas to absorb heat – the driving force of global warming.

Carbon dioxide is an odorless, tasteless, transparent gas that forms when people burn fuels, including coal, oil, gasoline and wood.

As Earth’s surface heats, one might think that the heat would just radiate back into space. But, it’s not that simple. The atmosphere stays hotter than expected mainly due to greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and atmospheric water vapor, which all absorb outgoing heat. They’re called “greenhouse gases” because, not unlike the glass of a greenhouse, they trap heat in Earth’s atmosphere and radiate it back to the planet’s surface. The idea that the atmosphere trapped heat was known, but not the cause.

Foote conducted a simple experiment. She put a thermometer in each of two glass cylinders, pumped carbon dioxide gas into one and air into the other and set the cylinders in the Sun. The cylinder containing carbon dioxide got much hotter than the one with air, and Foote realized that carbon dioxide would strongly absorb heat in the atmosphere.

Foote’s discovery of the high heat absorption of carbon dioxide gas led her to conclude that “… if the air had mixed with it a higher proportion of carbon dioxide than at present, an increased temperature” would result.

A few years later, in 1861, the well-known Irish scientist John Tyndall also measured the heat absorption of carbon dioxide and was so surprised that something “so transparent to light” could so strongly absorb heat that he “made several hundred experiments with this single substance.”

Tyndall also recognized the possible effects on the climate, saying “every variation” of water vapor or carbon dioxide “must produce a change of climate.” He also noted the contribution other hydrocarbon gases, such as methane, could make to climate change, writing that “an almost inappreciable addition” of gases like methane would have “great effects on climate.”

Humans were already increasing carbon dioxide in the 1800s

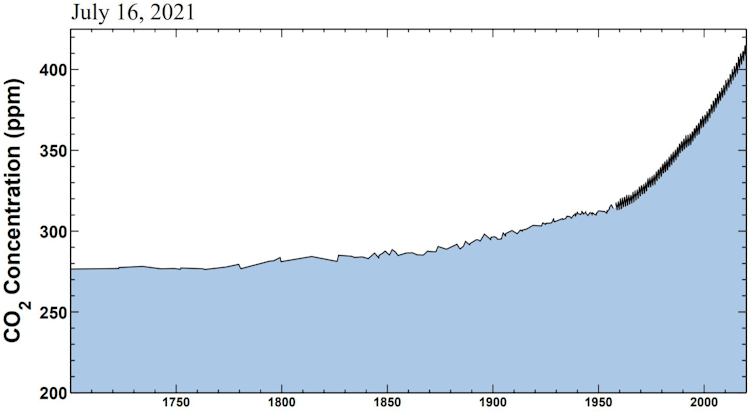

By the 1800s, human activities were already dramatically increasing the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Burning more and more fossil fuels – coal and eventually oil and gas – added an ever-increasing amount of carbon dioxide into the air.

The first quantitative estimate of carbon dioxide-induced climate change was made by Svante Arrhenius, a Swedish scientist and Nobel laureate. In 1896, he calculated that “the temperature in the Arctic regions would rise 8 or 9 degrees Celsius if carbon dioxide increased to 2.5 or 3 times” its level at that time. Arrhenius’ estimate was likely conservative: Since 1900 atmospheric carbon dioxide has risen from about 300 parts per million to around 417 ppm as a result of human activities, and the Arctic has already warmed by about 3.8 C (6.8 F).

Nils Ekholm, a Swedish meteorologist, agreed, writing in 1901 that “The present burning of pit-coal is so great that if it continues … it must undoubtedly cause a very obvious rise in the mean temperature of the earth.” Ekholm also noted that carbon dioxide acted in a layer high in the atmosphere, above water vapor layers, where small amounts of carbon dioxide mattered.

All of this was understood well over a century ago.

Initially, scientists thought a possible small rise in the Earth’s temperature could be a benefit, but these scientists could not envision the coming huge increases in fossil fuel use. In 1937, English engineer Guy Callendar documented how rising temperatures correlated with rising carbon dioxide levels. “By fuel combustion, man has added about 150,000 million tons of carbon dioxide to the air during the past half century,” he wrote, and “world temperatures have actually increased ….”

A warning to the president in 1965, and then …

In 1965, scientists warned U.S. President Lyndon Johnson about the growing climate risk, concluding: “Man is unwittingly conducting a vast geophysical experiment. Within a few generations he is burning the fossil fuels that slowly accumulated in the earth over the past 500 million years.” The scientists issued clear warnings of high temperatures, melting ice caps, rising sea levels and acidification of ocean waters.

In the half-century that has followed that warning, more of the ice has melted, sea level has risen further and acidification due to ever increasing absorption of carbon dioxide forming carbonic acid has become a critical problem for ocean-dwelling organisms.

Scientific research has vastly strengthened the conclusion that human-generated emissions from the burning of fossil fuels are causing dangerous warming of the climate and a host of harmful effects. Politicians, however, have been slow to respond. Some follow an approach that has been used by some fossil fuel companies of denying and casting doubt on the truth, while others want to “wait and see,” despite the overwhelming evidence that harm and costs will continue to rise.

In fact, reality is now fast overtaking scientific models. The megadrought and heat waves in the western U.S., record high temperatures and zombie fires in Siberia, massive wildfires in Australia and the U.S. West, relentless, intense Gulf Coast and European rains and more powerful hurricanes are all harbingers of increasing climate disruption.

The world has known about the warming risk posed by excessive levels of carbon dioxide for decades, even before the invention of cars or coal-fired power stations. A rare female scientist in her time, Eunice Foote, explicitly warned about the basic science 165 years ago. Why haven’t we listened more closely?

Neil Anderson, a retired chemical engineer and chemistry teacher, contributed to this article.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Sylvia G. Dee, Assistant Professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, Rice University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of AmericanScience.org.