Barry Komisaruk, Rutgers University and María Cruz Rodríguez del Cerro, UNED - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia

“Sexual Response in the Human Female,” popularly known as the “Kinsey Report,” generated an international sensation in 1953, revolutionizing the way society thinks of sex.

One particular statement in the book regarding the cervix, however, has been misinterpreted leading to a misconception that persists today. On page 584, Kinsey states, “All of the clinical and experimental data show that the surface of the cervix is the most completely insensitive part of the female genital anatomy.”

Along with our colleague, physician Irwin Goldstein, we are specialists in neuroscience and sexual medicine. We believe Kinsey’s statement has led healthcare providers to conclude, erroneously, that the cervix is devoid of sensory nerves and can be cut or removed without consequence.

A closer look at the data

The Kinsey investigators reported when the cervix was “gently stroked” with a “glass, metal or cotton-tipped probe,” only 5% of 878 women reported they could feel it. This data was the basis of Kinsey’s claim of cervical insensitivity.

However, when the investigators stimulated the cervix of the same women with “distinct pressure” using “an object larger than a probe,” 84% of the 878 women reported they could feel it. Kinsey’s conclusion did not take into account his own significant finding.

The sensate cervix

There is extensive clear data from diverse sources that women can certainly feel stimulation of the cervix. Women commonly report they can feel the Pap smear procedure in which tissues are scraped from the cervix surface.

Many women undergoing cervical dilation for insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) report pain.

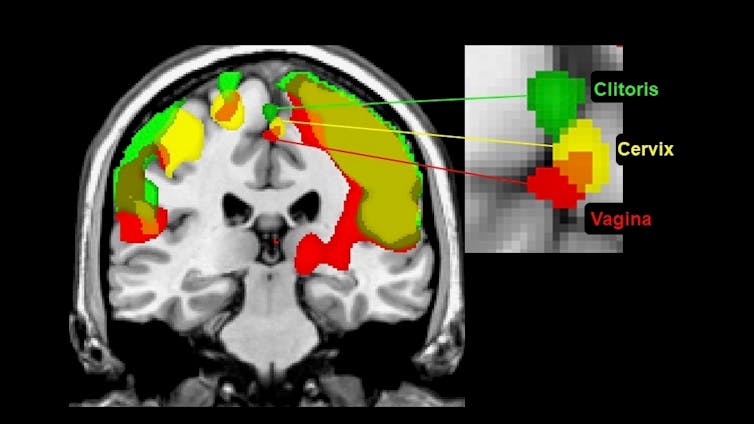

In a functional MRI study, when women stimulated their cervix, the same part of their brain responded as when they stimulated their clitoris or vagina. They also reported they could feel each region distinctly. The contribution of the cervix to orgasm is described in popular media and some women report cervical-stimulated orgasms as having qualities different from clitoral or vaginal-stimulated orgasms.

Surgery and the cervix

Researchers also know the cervix is sensate based on the effects surgery can have on it. While well-intentioned medical procedures are designed to treat significant gynecological problems, in the process, they can cause damage to the nerve supply of the cervix.

According to one study, when the cervix is saved in a “sub-total” hysterectomy, women are significantly more likely to continue experiencing orgasms than when the cervix is removed in a “total” hysterectomy.

Another review of recent hysterectomy procedures, though, found no significant difference in the effects on sexual response between the two types of surgery. However, while the majority of the women reported an improvement in their sexual response, due to the resolution of the problem that necessitated their hysterectomy, in almost every one of the 22 reports reviewed, multiple women stated that their genital sensations were diminished. The discrepancies in the literature might well be due to different women’s preferred source of stimulation.

Some women undergoing an often-used loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) for the excision of lesions on the cervix report sexual side effects. Some women describe a consequent distressing loss of orgasm and erotic feeling in body regions including the clitoris and vagina. The procedure, in which a cone-shaped volume of cervix is burned away using a cauterizing wire loop, may be causing destruction of nerve pathways that normally convey genital sensation to the brain.

In another common surgical procedure for treatment of stress urinary incontinence, surgeons insert a mesh “mid-urethral sling” between the vagina and the urethra to produce a slight bend in the urethra, thereby adding resistance to the flow of urine. The sling may damage nerves that carry sensation from the vagina and cervix. Indeed, some women report reduced orgasm satisfaction after surgery.

Talk to your doctor

Doctors should be aware that three pairs of nerves – pelvic, hypogastric and vagus – convey sensation from the cervix to the brain. If any of these nerves are compromised, it can profoundly affect sexual pleasure. If surgical treatment is necessary, doctors should attempt to avoid the location of critical nerve pathways to minimize sensory damage.

Patients and their health care providers are often reluctant to discuss sensitive issues, such as possible side effects relating to sexual pleasure. At the very least, doctors should inform their patients of the possible detrimental consequences of their proposed treatment.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]![]()

Barry Komisaruk, Distinguished Professor of Psychology, Rutgers University and María Cruz Rodríguez del Cerro, Professor of Psychobiology, UNED - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in the article are solely those of their authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of AmericanScience.org.