The Arctic can feel like a far-off place, disconnected from daily life if you aren’t one of the 4 million people who live there. Yet, the changes underway in the Arctic as temperatures rise can profoundly affect lives around the world.

Coastal flooding is worsening in many communities as Arctic glaciers and the Greenland Ice Sheet send meltwater into the oceans. Heat-trapping gases released by Arctic wildfires and thawing tundra mix quickly in the air, adding to human-produced emissions that are warming the globe. Unusual and extreme weather events, pressure on food supplies and intensifying threats from wildfire and related smoke can all be influenced by changes in the Arctic.

In the 2024 Arctic Report Card, released Dec. 10, we brought together 97 scientists from 11 countries, with expertise ranging from wildlife to wildfire and sea ice to snow, to report on the state of the Arctic environment.

They describe the rapid changes they’re witnessing across the Arctic, and the consequences for people and wildlife that touch every region of the globe.

Pace of change in the Arctic accelerates

The Arctic of today looks stunningly different from the Arctic of even one to two decades ago. Over the Arctic Report Card’s 19 years, we and the many contributing authors to the report have watched the pace of environmental change accelerate and the challenges become more complex.

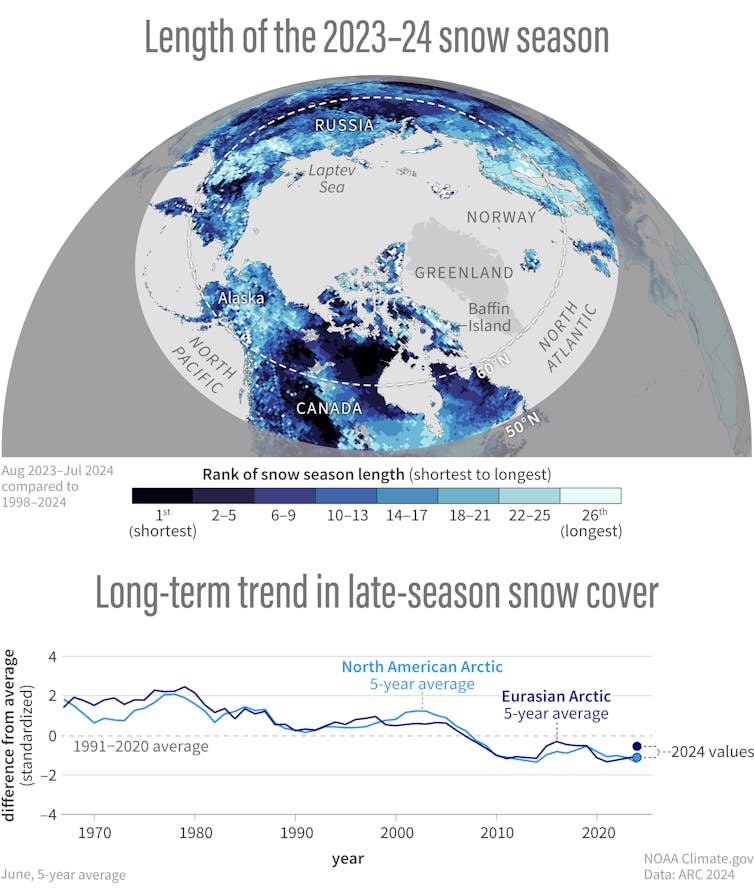

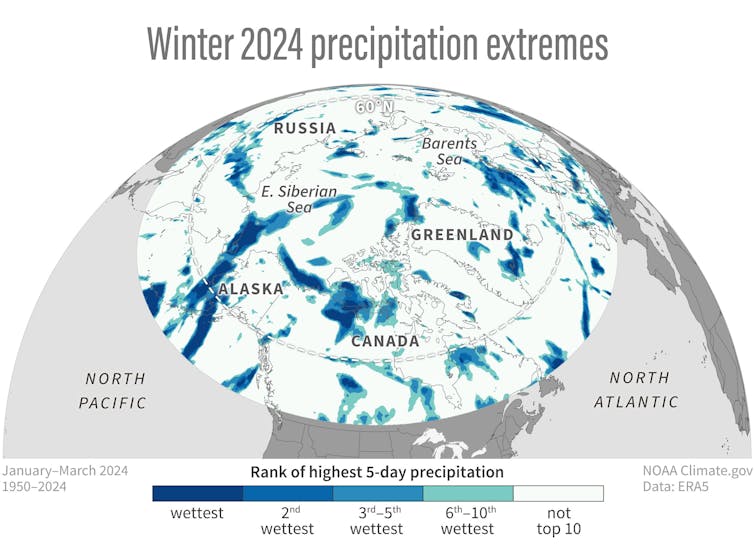

For the past 15 years, the Arctic snow season has been one to two weeks shorter than it was historically, shifting the timing and character of the seasons.

Shorter snow seasons can challenge plants and animals that depend on regular seasonal changes. Longer snow-free seasons can also reduce water resources from snowmelt earlier in spring or summer and increase the possibility of drought.

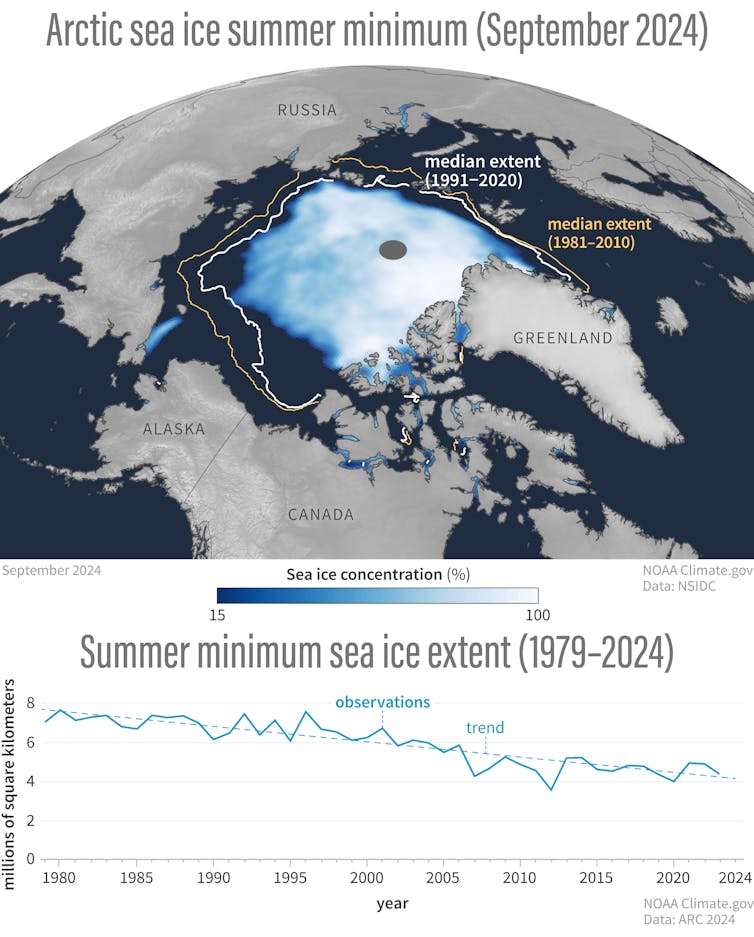

The extent of sea ice, an important habitat for many animals, has declined in ways that make today’s mostly thin and seasonal sea ice landscape unrecognizable compared with the thicker and more extensive sea ice of decades past.

With a shorter sea ice season, the dark ocean surface is exposed and can absorb and store more heat during summer, which then adds to air and ocean temperature increases. This aligns with observations of long-term warming for Arctic surface ocean waters. Sea ice-dependent animals can also be forced ashore or into longer fasting seasons. The Arctic shipping season is also lengthening, with rapidly increasing shipping traffic each summer.

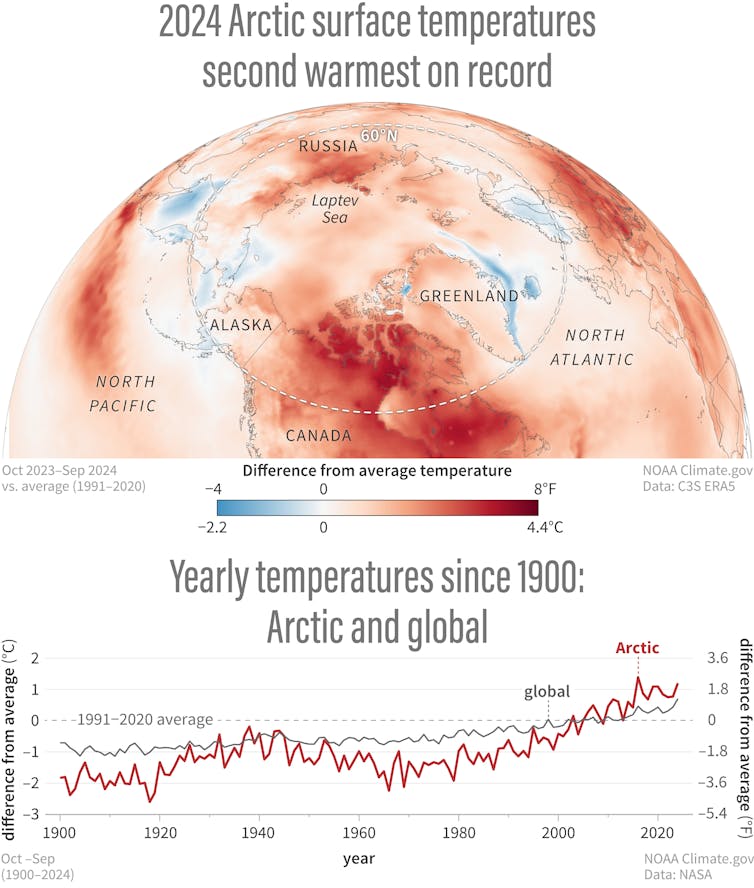

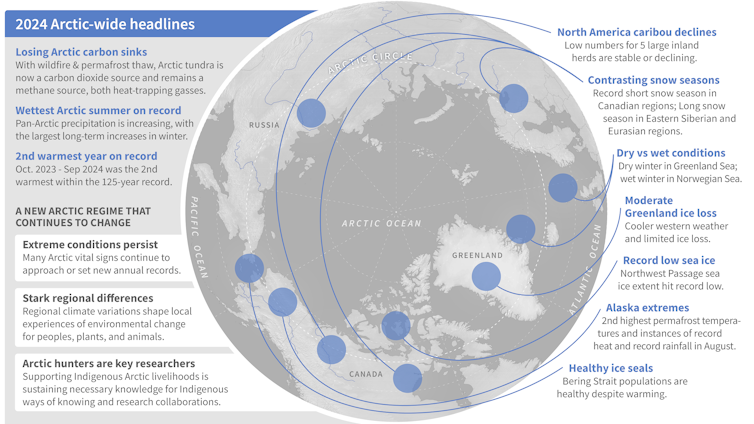

Overall, 2024 brought the second-warmest temperatures to the Arctic since measurements began in 1900, and the wettest summer on record.

Arctic tundra becomes a carbon source

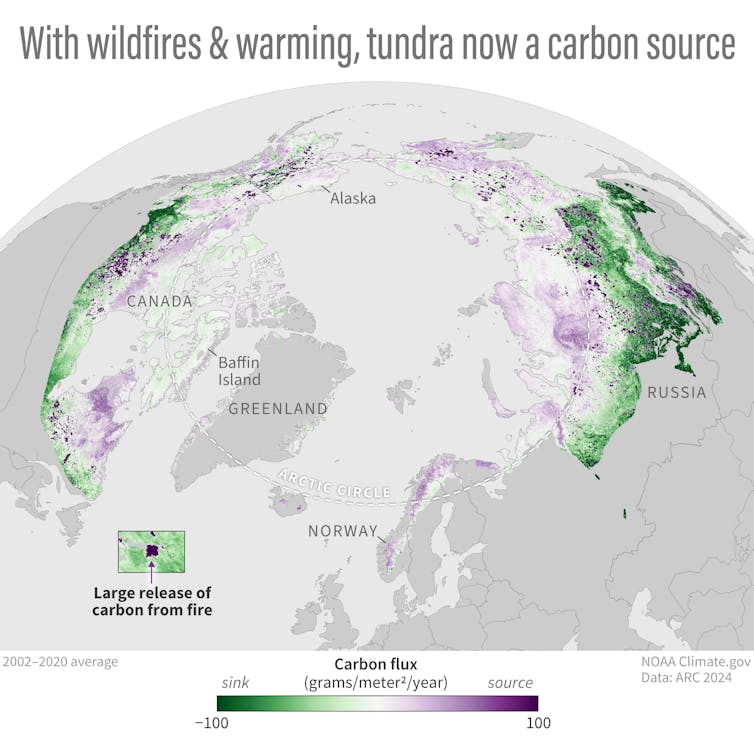

For thousands of years, the Arctic tundra landscape of shrubs and permafrost, or frozen ground, has acted as a carbon dioxide sink, meaning that the landscape was taking up and storing this gas that would otherwise trap heat in the atmosphere.

But permafrost across the Arctic has been warming and thawing. Once thawed, microbes in the permafrost can decompose long-stored carbon, breaking it down into carbon dioxide and methane. These heat-trapping gases are then released to the atmosphere, causing more global warming.

Wildfires have also increased in size and intensity, releasing more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and the wildfire season has grown longer.

These changes have pushed the tundra ecosystem over an edge. Susan Natali and colleagues found that the Arctic tundra region is now a source – not a sink, or storage location – for carbon dioxide. It was already a methane source because of thawing permafrost.

The Arctic landscape’s natural ability to help to buffer human heat-trapping gasses is ending, adding to the urgency to reduce human emissions.

Stark regional differences make planning difficult

The Arctic Report Card covers October through September each year, and 2024 was the second-warmest year on record for the Arctic. Yet, the experience for people living in the Arctic can feel like regional or seasonal weather whiplash.

Stark regional differences in weather can make planning difficult and challenge familiar seasonal patterns. These include very different conditions in neighboring areas or big changes from one season to another.

For example, some areas across North America and Eurasia experienced more winter snow than usual during the past year. Yet, the Canadian Arctic experienced the shortest snow season in the 26-year record. Early loss of winter snow can strain water resources and may exacerbate dry conditions that can add to fire danger.

Summer across the Arctic was the third warmest ever observed, and areas of Alaska and Canada experienced record daily temperatures during August heat waves. Yet, residents of Greenland’s west coast experienced an unusually cool spring and summer. Though the Greenland Ice Sheet continued its 27-year record of ice loss, the loss was less than in many recent years.

Ice seals, caribou and people feeling the change

Rapid Arctic warming also affects wildlife in different ways.

As Lori Quakenbush and colleagues explain in this year’s report, Alaska ice seal populations, including ringed, bearded, spotted and ribbon seals, are currently healthy despite sea ice decline and warming ocean waters in their Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort sea habitats.

However, ringed seals are eating more saffron cod rather than the more nutritious Arctic cod. Arctic cod are very sensitive to water temperature. As waters warm, they shift their range northward, becoming less abundant on the continental shelves where the seals feed. So far, negative effects on seal populations and health are not yet apparent.

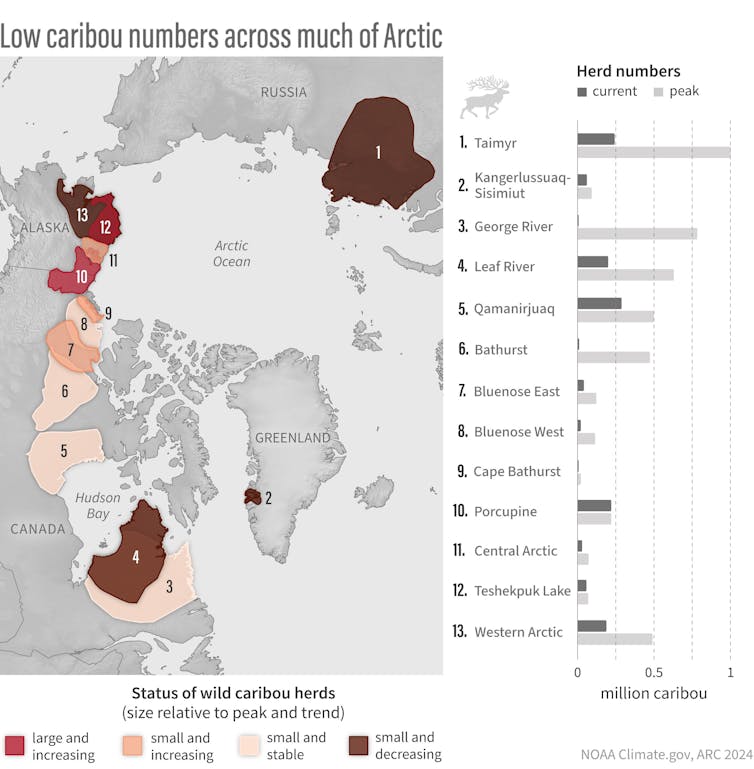

On land, large inland caribou herds are overwhelmingly in decline. Climate change and human roads and buildings are all having an impact. Some Indigenous communities who have depended on specific herds for millennia are deeply concerned for their future and the impact on their food, culture and the complex and connected living systems of the region. Some smaller coastal herds are doing better.

Indigenous peoples in the Arctic have deep knowledge of their region that has been passed on for thousands of years, allowing them to flourish in what can be an inhospitable region. Today, their observations and knowledge provide vital support for Arctic communities forced to adapt quickly to these and other changes. Supporting Indigenous hunters and harvesters is by its very nature an investment in long-term knowledge and stewardship of Arctic places.

Action for the Arctic and the globe

Despite global agreements and bold targets, human emissions of heat-trapping gasses are still at record highs. And natural landscapes, like the Arctic tundra, are losing their ability to help reduce emissions.

Simultaneously, the impacts of climate change are growing, increasing Arctic wildfires, affecting buildings and roads as permafrost thaws, and increasing flooding and coastal erosion as sea levels rise. The affects are challenging plants and animals that people depend on.

Our 2024 Arctic Report Card continues to ring the alarm bell, reminding everyone that minimizing future risk – in the Arctic and in all our hometowns – requires cooperation to reduce emissions, adapt to the damage and build resilience for the future. We are in this together.![]()

Twila A. Moon, Deputy Lead Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado Boulder; Matthew L. Druckenmiller, Research Scientist, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado Boulder, and Rick Thoman, Alaska Climate Specialist, University of Alaska Fairbanks

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.