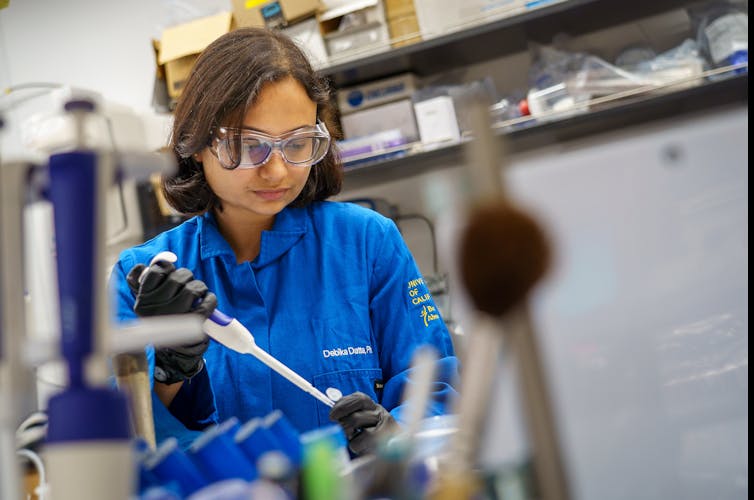

Jonathan K. Pokorski, University of California, San Diego and Debika Datta, University of California, San Diego

Water pollution is a growing concern globally, with research estimating that chemical industries discharge 300-400 megatonnes (600-800 billion pounds) of industrial waste into bodies of water each year.

As a team of materials scientists, we’re working on an engineered “living material” that may be able to transform chemical dye pollutants from the textile industry into harmless substances.

Water pollution is both an environmental and humanitarian issue that can affect ecosystems and human health alike. We’re hopeful that the materials we’re developing could be one tool available to help combat this problem.

Engineering a living material

The “engineered living material” our team has been working on contains programmed bacteria embedded in a soft hydrogel material. We first published a paper showing the potential effectiveness of this material in Nature Communications in August 2023.

The hydrogel that forms the base of the material has similar properties to Jell-O – it’s soft and made mostly of water. Our particular hydrogel is made from a natural and biodegradable seaweed-based polymer called alginate, an ingredient common in some foods.

The alginate hydrogel provides a solid physical support for bacterial cells, similar to how tissues support cells in the human body. We intentionally chose this material so that the bacteria we embedded could grow and flourish.

We picked the seaweed-based alginate as the material base because it’s porous and can retain water. It also allows the bacterial cells to take in nutrients from the surrounding environment.

After we prepared the hydrogel, we embedded photosynthetic – or sunlight-capturing – bacteria called cyanobacteria into the gel.

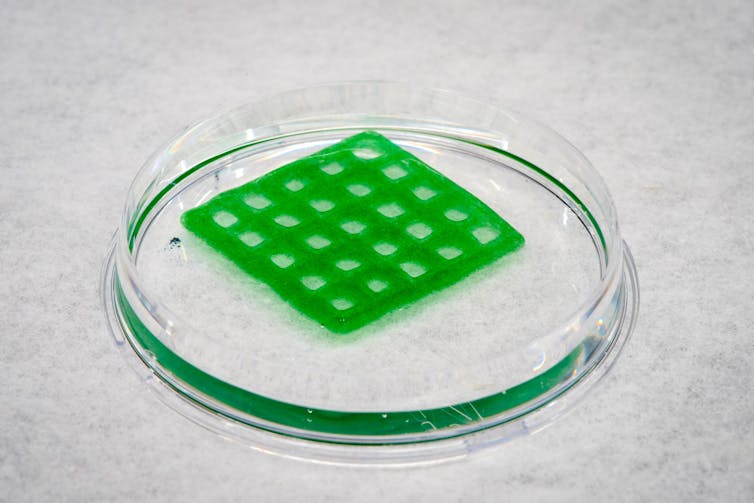

The cyanobacteria embedded in the material still needed to take in light and carbon dioxide to perform photosynthesis, which keeps them alive. The hydrogel was porous enough to allow that, but to make the configuration as efficient as possible, we 3D-printed the gel into custom shapes – grids and honeycombs. These structures have a higher surface-to-volume ratio that allow more light, CO₂ and nutrients to come into the material.

The cells were happy in that geometry. We observed higher cell growth and density over time in the alginate gels in the grid or honeycomb structures when compared with the default disc shape.

Cleaning up dye

Like all other bacteria, cyanobacteria has different genetic circuits, which tell the cells what outputs to produce. Our team genetically engineered the bacterial DNA so that the cells created a specific enzyme called laccase.

The laccase enzyme produced by the cyanobacteria works by performing a chemical reaction with a pollutant that transforms it into a form that’s no longer functional. By breaking the chemical bonds, it can make a toxic pollutant nontoxic. The enzyme is regenerated at the end of the reaction, and it goes off to complete more reactions.

Once we’d embedded these laccase-creating cyanobacteria into the alginate hydrogel, we put them in a solution made up of industrial dye pollutant to see if they could clean up the dye. In this test, we wanted to see if our material could change the structure of the dye so that it went from being colored to uncolored. But, in other cases, the material could potentially change a chemical structure to go from toxic to nontoxic.

The dye we used, indigo carmine, is a common industrial wastewater pollutant usually found in the water near textile plants – it’s the main pigment in blue jeans. We found that our material took all the color out of the bulk of the dye over about 10 days.

This is good news, but we wanted to make sure that our material wasn’t adding waste to polluted water by leaching bacterial cells. So, we also engineered the bacteria to produce a protein that could damage the cell membrane of the bacteria – a programmable kill switch.

The genetic circuit was programmed to respond to a harmless chemical, called theophylline, commonly found in caffeine, tea and chocolate. By adding theophylline, we could destroy bacterial cells at will.

The field of engineered living materials is still developing, but this just means there are plenty of opportunities to develop new materials with both living and nonliving components.![]()

Jonathan K. Pokorski, Professor of Nanoengineering, University of California, San Diego and Debika Datta, Postdoctoral Scholar in Nanoengineering, University of California, San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.